Experimenting with Environmental Anthropology in "Laboratory for Other Worlds"

Review of Laboratory for Other Worlds at the Bellevue Arts Museum

Written by Teen Writer Olivia Qi and edited by Teen Editor Aamina Mughal

Climate change is real and dangerous, but you do not need this article to tell you that. There is an abundance of scientific knowledge about environmental collapse, so why is it so hard for our society to develop cultural responses and policies that prioritize the environment? Patte Loper, the artist behind Laboratory for Other Worlds at the Bellevue Arts Museum, takes French philosopher Bruno Latour’s stance: we need art to translate scientific data into political knowledge. In the “Laboratory”, Loper experiments with connecting the human world and other worlds of plants, animals, spirits, and land. She uses her distinct visual language to encourage unity between humans and nonhumans, proposing a spiritual solution to climate change.

“There is another world but it is in this one,” reads the Paul Éluard quote on the wall facing the exhibit’s entrance. Entering the exhibit, I understood that Loper’s art belongs to that other world, the world of nature. Loper’s three Paintings for Trees (2022), which look like silver scraps on sticks, hang on a wall behind little sculptures of clay, cement, glass jars, dirt, and wood. These little sculptures are Plant Companion Devices (2022), a Painting for Plants (2021), and Lichen Incubator (2022). The Plant Companion Devices are relatively small and made of clay and sticks, and some have a tangled mass of cardboard reminiscent of tree roots. The Lichen Incubator drips water through bendy tubes into glass flasks for a rock or piece of wood.

All the sculptures fall under the category of “Plant Communication Devices,” which Loper believes to be important because humans communicate with plants all the time. We talk to plants, observe their postures to see if they need more water or food, and Loper translates our nonscientific communication into a visual form with humble materials and an imperfect aesthetic. By building a closer, spiritual relationship with plants, our society can give plants a space in our culture instead of killing them for the sake of environmentally disastrous development.

I found it difficult to match sculptures with their titles because their labels were clumped together away from their corresponding works. I spent a good fifteen minutes trying to match the sculptures to their titles, but that made me think critically about Loper’s symbolism, which helped me interpret her more complex works in the rest of the exhibit.

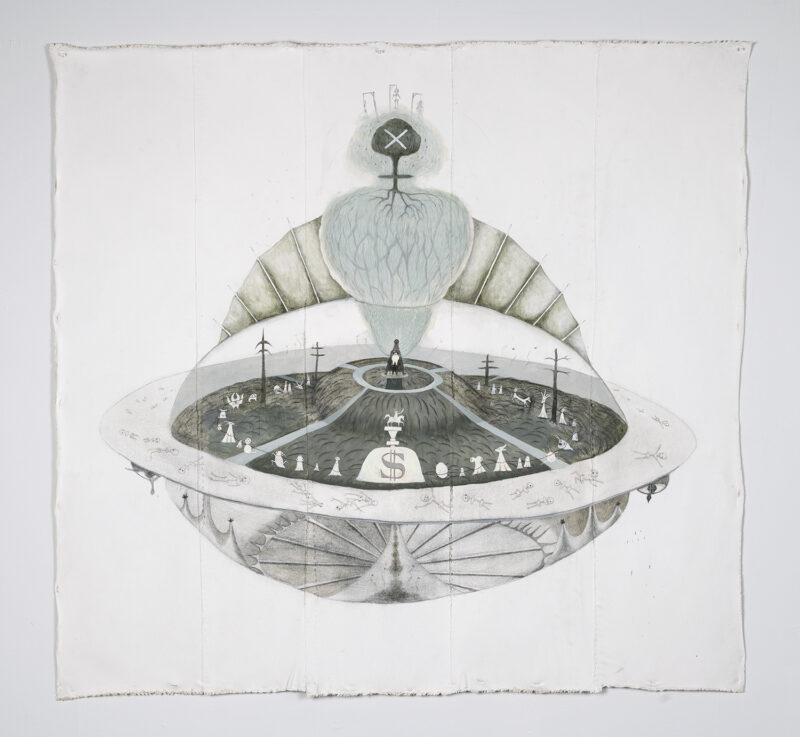

Loper also created tapestry maps with light illustrations inspired by the All Faiths Cemetery in New York. She uses muted grays and green against three white canvases to paint Heaven (2022), Earth (2022), and Hell (2022). In each of the tapestries, people are surrounded by webs, tubes with eyes, skeletons, fantastical animals, and plants. She also made a Psychic Corporeal Map of Bellevue, WA (2022), which depicts Bellevue as a creature with claws, showing the city as a whole being. It creates a body-territory, the idea that the land where our family members are buried is an extension of our bodies.

Loper explores the concept of burial sites as extensions of the human body where the past, present, and future are one. Loper uses a quote from Black Elk, a 19th and 20th-century medicine man of the Oglala Lakota people, in a wall label: “Anywhere can be the center of the earth.” The belief that everything exists at every moment and surrounds everything else is old wisdom for Native Americans, but Loper connects it to a Christian lexicon by using a triptych structure familiar to white society. Specifically, her tapestries reminded me of Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (1515).

In the same room, Loper includes a study station in her exhibit with books about humans and the environment, a glossary, and plants. I found the glossary quite helpful in understanding Loper’s art because it defined technical words like “earthcraft,” “body-territory,” and “holobiome.” However, I felt like the environmental anthropology books were a little overkill. Loper understandably wanted people to have as much context of her work as possible, but the effort ended up being fruitless, as I didn’t want to take the time to read those books. Part of my choice to not read was also analysis paralysis, and if Loper had lifted quotes from the books or only provided one shorter book, I would have read. Loper encouraged people to study the books and take notes on notecards she provided, but it seemed like many people felt the same way I did about the books: most of the notecards were scribbled on by little kids.

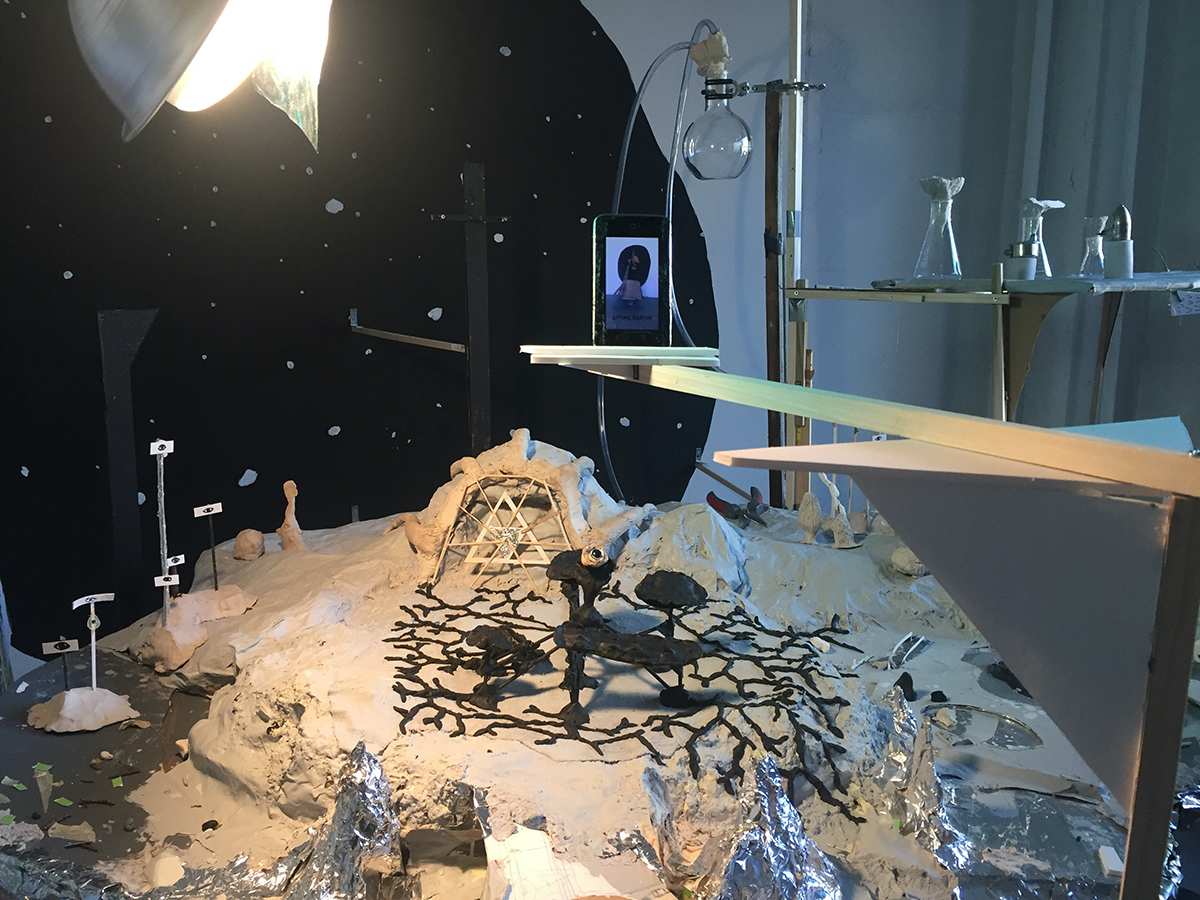

The map of Bellevue was outshone by a huge multimedia installation next to it, Cthonos (2022). “Cthonos” comes from the Greek word “chthonios,” meaning “of the earth and seas.” It is easily the most complex work in the exhibit, but I found it fairly understandable after learning about Loper’s other art. A tabletop represents the barrier between the human realm and the underground, and around it is a mannequin head and pieces similar to the Plant Communication Devices earlier in the exhibit. I spotted a “Lichen Incubator” and a few “Paintings for Trees”. They make the desk look like an altar, emphasizing the needed respect for the spiritual connection of humans and nonhumans.

An enormous abstract snail sits in front of the desk, a tangled web in its neck representing underground mycorrhizal networks. The network is made of salvaged art from Loper’s previous installations, which she lets break so it can be reused like everything in nature is.

The whole installation is bathed in magenta light and the sounds of bells, crackles, and static. A video projected onto the wall and two smaller screens near the snail teaches viewers how we humans are part of the “Cthonos” as well, and we must accept our connected identities to thrive.

Loper’s art is more than art; it is a whole new way of thinking. I left the exhibit seeing the world through a new perspective, recognizing the connections between me, trees outside, the building, and museum docents passing by. It is tempting to dismiss concepts like plant communication and oneness as hippie rhetoric, but Loper’s art makes them urgently relevant to our world. Visit the “Laboratory” with an open mind, experiment with environmental anthropology, and bring our society a step closer to solving the climate crisis.

Laboratory for Other Worlds took place at the Bellevue Arts Museum on May 20, 2022 — January 8, 2023. For more information see here.

Lead Photo: Patte Loper's Quiet Counrty, 2021. Photo courtesy of Mark Woods Studio.

The TeenTix Newsroom is a group of teen writers led by the Teen Editorial Staff. For each review, Newsroom writers work individually with a teen editor to polish their writing for publication. The Teen Editorial Staff is made up of 6 teens who curate the review portion of the TeenTix blog. More information about the Teen Editorial Staff can be found HERE.

The TeenTix Press Corps promotes critical thinking, communication, and information literacy through criticism and journalism practice for teens. For more information about the Press Corps program see HERE.