Maybe the Real Banana Was the Friends We Made Cry Along the Way

Review of Make Banana Cry at On the Boards

Written by TeenTix Newsroom Writer Milo Miller and edited by Teen Editorial Staff Member Audrey Gray

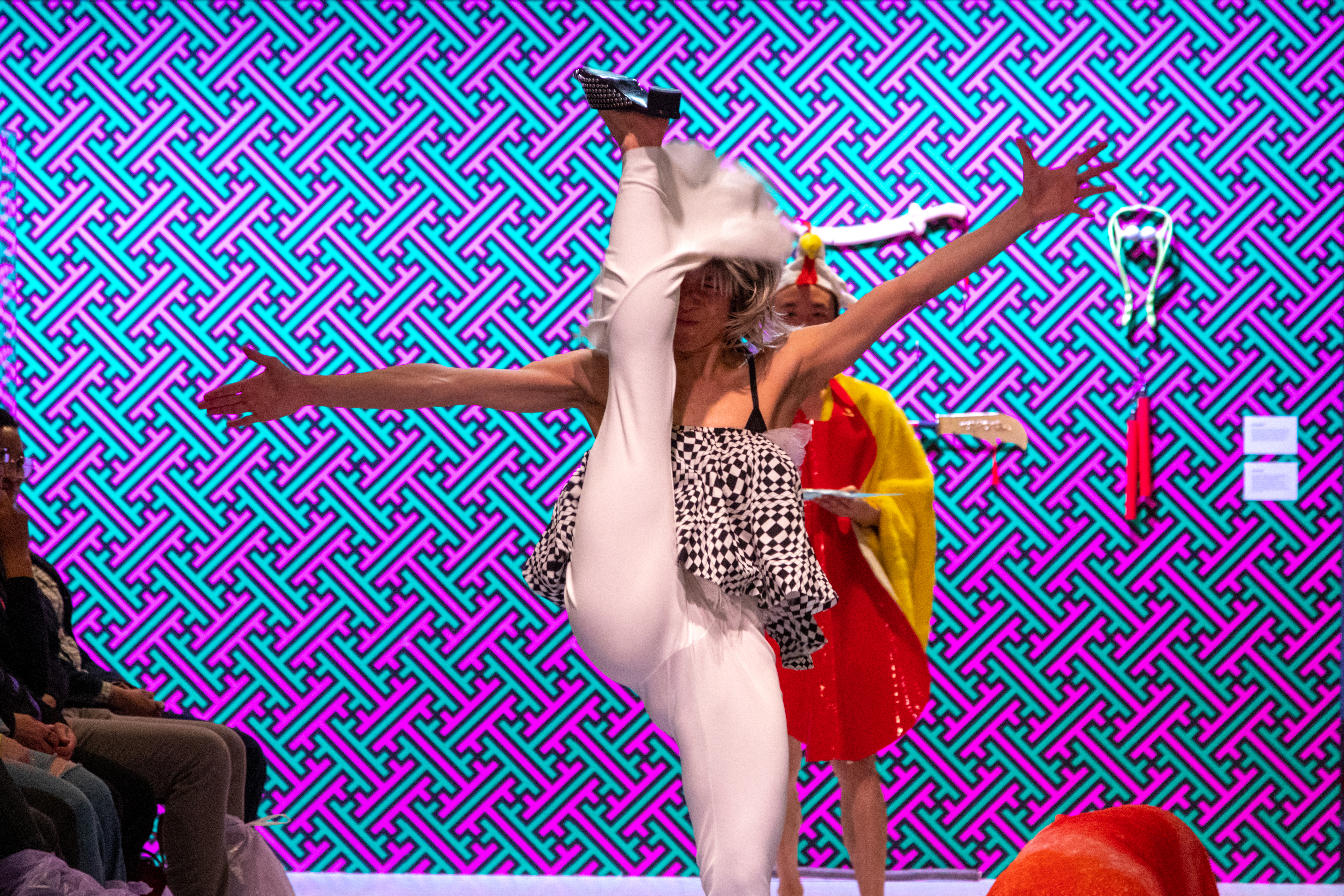

At On the Boards’ show Make Banana Cry, the audience is part of the stage. It is an uncomfortably post-modern, avante-garde performance disguised as a simple dance and fashion show, set on a runway stage. Performers strut down paths patterned with Buddhist swastikas, in various states of dress and undress, holding a collection of props and using them in different ways. Sometimes they march slowly—sometimes to the point of unmoving—and sometimes they are explosively radiant in their color, movement, and expressiveness. Under the helm of producer/performer power duo Andrew Tay and Stephen Thompson, the six performers are accompanied by an ever-changing set of soundtracks, consisting of everything from Miss Saigon to frantic pop songs to what seems to be the rhythmic beating of helicopter propellers. This collection of sounds and cues is not random but very intentional, for the show is meant to be an out-of-the-box method for paralyzing a largely white audience with symbols and themes commonly associated with the appropriation of Asian cultures. The auditory design and wild costume choices enhance the discomfort put upon the audience. However, as the show experiments with imagination, it also discovers that entertainment and creativity do not always go hand in hand.

Upon walking into the theater, audience members are handed plastic foot covers so their shoes don’t scuff the stage; these remain on for the entirety of the performance. Then, the audience examines various items such as Chinese checkerboards and towering sculptures of oversized cup noodle packages before taking their seats. The audience then sits in silence as the performance slowly begins, and then rapidly escalates. The performers march, run, or crawl down the runway toting a variety of different props and wearing strange costumes that bend the definition of clothes. The costumes are continuously weird and eccentric—sometimes coherently so and sometimes like a jumble of the strangest outfits ever worn. The actors confront, speak to, and hand things to audience members, who are scattered around in clusters of rows throughout the stage. The goal of the actors throughout these interactions is to challenge the audience’s beliefs and ideas via motifs. However, the boldness, force, enthusiasm, and nakedness of the performers often serve less as vehicles for metaphor and more so as a visceral shock to the “universal Western prejudice” mentioned by the show’s program. As the show veers off the rails, the performers’ goals are put on display: to illustrate a history of racism against Asian cultures and to boast their own Asian-ness in pride. The show’s themes are pleasantly startling but the execution of them is ultimately unsustainable.

For the time they are able to keep the magic alive, the show generally pulls off the audio-visual feat it set out to accomplish. The performers remain serious and unwavering, from their emergence onto the low-lit stage in parkas and scarves to the final curtain call, whether they’re staggering around pregnant with a giant metal bowl on their belly or dramatically sliding in on their knees and proposing to audience members. This tone comes in large part from the point of the performance. Every symbol is associated with some part of an Asian culture that has been either repressed or made into a stereotype, and the show, as forceful as it is, has every intention of letting its audience know how much the symbols mean, even when they would rather turn away. When judging it by its ability to pull off what it set out to do, Make Banana Cry entirely succeeds. If Make Banana Cry, this bootie-wearing, stage-sitting experience, is anything, then it is most certainly off-putting from the very beginning. Beyond its deep dive into the forest of Asian stereotypes, it wishes to overturn, the performance is unorthodox compared to any other form of creative art.

Yet this raises a problem. Make Banana Cry is an assault on the senses, but it's sheer craziness and serious whimsy detract from the point it’s trying to make. With so much (or, sometimes, so little) going on, the disparate weirdness of the show detracts from its meaning—there’s too much to go over one’s head. Every creative choice, from the costuming to the soundtrack, blares loudly, seemingly an alarm to shatter the tension in the audience. Every movement screams, for better or for worse.

Unfortunately, the show lacks the substance to make up for its slim runtime of an hour. From minutes spent in complete silence or lacking in any movement whatsoever, to a repetitive march filled with actions and mimes that blend together too quickly, the performance feels awfully one-note. Because the audience’s attention is held by the anticipation of what will happen next, when the show fails to pay off on its ever-so-carefully constructed building, it rapidly loses steam and entertainment value. Make Banana Cry is rarely new or unique past the introductory section; the performers’ poses, walks, and props change, but the meaning all feels the same. As powerful as it is, the show regularly loses its audience, only to once again build up anticipation that will ultimately be disappointed.

Though Make Banana Cry advertises itself as a dance performance, calling it so is stretching it a bit. The performers do not dance; rather, they circle the runway repeatedly, often at very slow speeds with very little going on visually. The performance brings the audience into its special world, but ultimately the tradeoff is between an enjoyable show and a vehicle to make a point. However, from this flaw comes freedom. Make Banana Cry’s incoherence can actually be pleasant, most of the time. Its lack of narrative makes room for all kinds of creativity that would not have fit otherwise. It is sparkly, dashing, fun, and potent, and to constrict it to the mechanisms of a typical dance piece would be to douse its fiery imagination. But at the same time, it is simply too disparate to come together fully. Put together, the performance feels half-baked, as if many of its prop design and costume choices were improvised. This allows for fathomless freedom for the extremely talented artists involved, but it seriously decreases the audience’s enjoyment and engagement.

Make Banana Cry is not a show for the faint of heart, both because of the performers’ willingness to strip on stage and the hard truth it forces upon its viewers. But audience members willing to devote themselves to the show entirely will find they’ve come out of the theater not necessarily changed, but certainly with a lot more to think about, and with a great appreciation of the sheer explosive talent that went into making it.

Lead Photo Credit: Courtesy of Manuel Vasson, Andrew Tay in Make Banana Cry

The TeenTix Newsroom is a group of teen writers led by the Teen Editorial Staff. For each review, Newsroom writers work individually with a teen editor to polish their writing for publication. The Teen Editorial Staff is made up of 5 teens who curate the review portion of the TeenTix blog. More information about the Teen Editorial Staff can be found HERE.

The TeenTix Press Corps promotes critical thinking, communication, and information literacy through criticism and journalism practice for teens. For more information about the Press Corps program see HERE.