The Vivid and Horrifying Films of Tsai Ming-liang

Review of Rebels of the Neon God and The Hole directed by Tsai Ming-liang at Northwest Film Forum

Written by TeenTix Newsroom Writer Milo Miller and edited by Teen Editorial Staff Member Daphne Bunker

Tsai Ming-liang has a knack for filmmaking. The Taiwanese film director knows just where to place the camera to get the perfect frame. He knows when to cut a clip to achieve the maximum effect of its weight and emotion. But most of all, he understands how to craft a compelling story with engrossing characters and little to no dialogue or music. He sets his films to a backdrop of ambient rain and city noises, achieving a feeling that is sometimes calming and sometimes tense the whole way through.

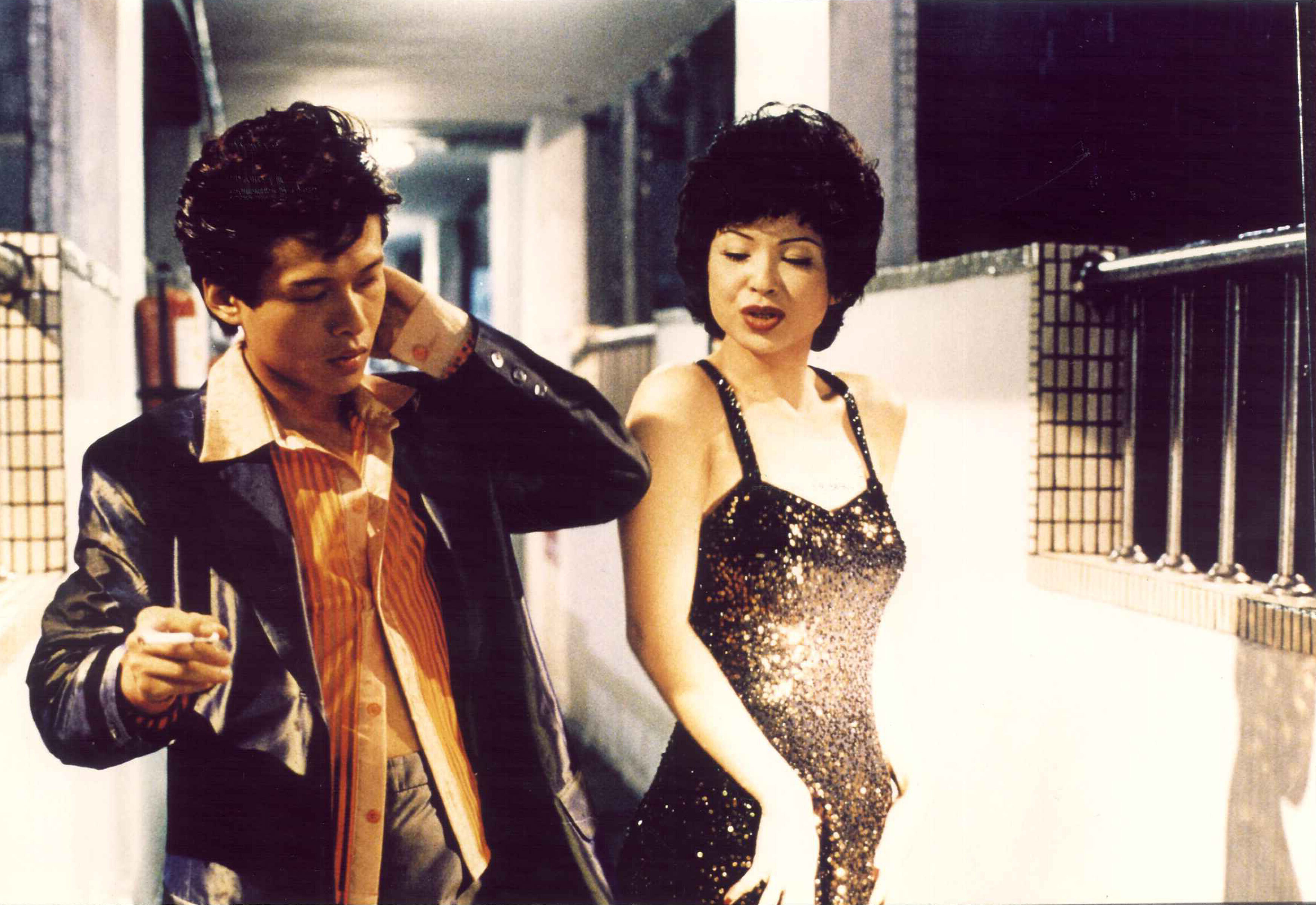

Rebels of the Neon God, which screened at Northwest Film Forum from January 10 to January 14, has some of the best-composed shots of the past few decades. It is both minimalist in its plot, characters, and sound design, and complex in its depiction of the ambiance of the city. The title of the film translated means: “Adolescent Nezha,” referring to the Chinese deity. At the beginning of the film, young student Hsaio Kang’s mother decides that her son is a reincarnation of Nezha, the “Neon God.” Throughout the film, we see Hsaio Kang through the lens of his relationship with this deity. Hsaio Kang, portrayed by the talented Lee Kang-sheng, does not think quite so highly of himself. Instead, after quitting cram school to collect the refund, he slinks around the city, stalking the petty crimes and romances of Ah Tze and his friend Ping. He never directly intervenes with any of the people he is trailing, but their interactions (either subtle or overt) leave lasting emotional effects on him.

Though it’s a different film, Lee Kang-sheng reprises his performance of Hsaio Kang (or some version of him) in his subsequent film The Hole, which screened at Northwest Film Forum from January 17 to January 21. In the film, a mysterious disease has struck Taiwan causing its inhabitants who catch it to become increasingly insect-like, including crawling and hiding in dark, damp places. Two tenants, including struggling food store owner Kang, refuse to leave their apartments and are tormented by a hole in the floor connecting their two homes. The Hole is a freakishly intense film that contains brooding cinematography by Liao Pen-jung, long shots of its suffering characters, and the constant pattering of rain outside, downright terrifying, onto a desolate Taiwan. Tsai Ming-liang’s filmmaking style has often been called “bittersweet”—but The Hole is nothing but bitter. All sweetness and sentimentality are put aside in the hopes of elevating the film’s depiction of human despair. It works. Tsai Ming-liang makes his films feel dirty like there’s a coat of mire that, throughout the runtime, you want to desperately scrape off the screen, until you find you cannot. Through murky apartments, drowned in pools of reeking water from mysterious leaks, to the disease that makes its victims act like cockroaches, he is the master of making a movie feel like it needs to be cleaned. He has the uncanny ability to alter the way the viewer looks at his world through the appearance and feeling of grime. In this way, another layer of bleakness is added to his unique films.

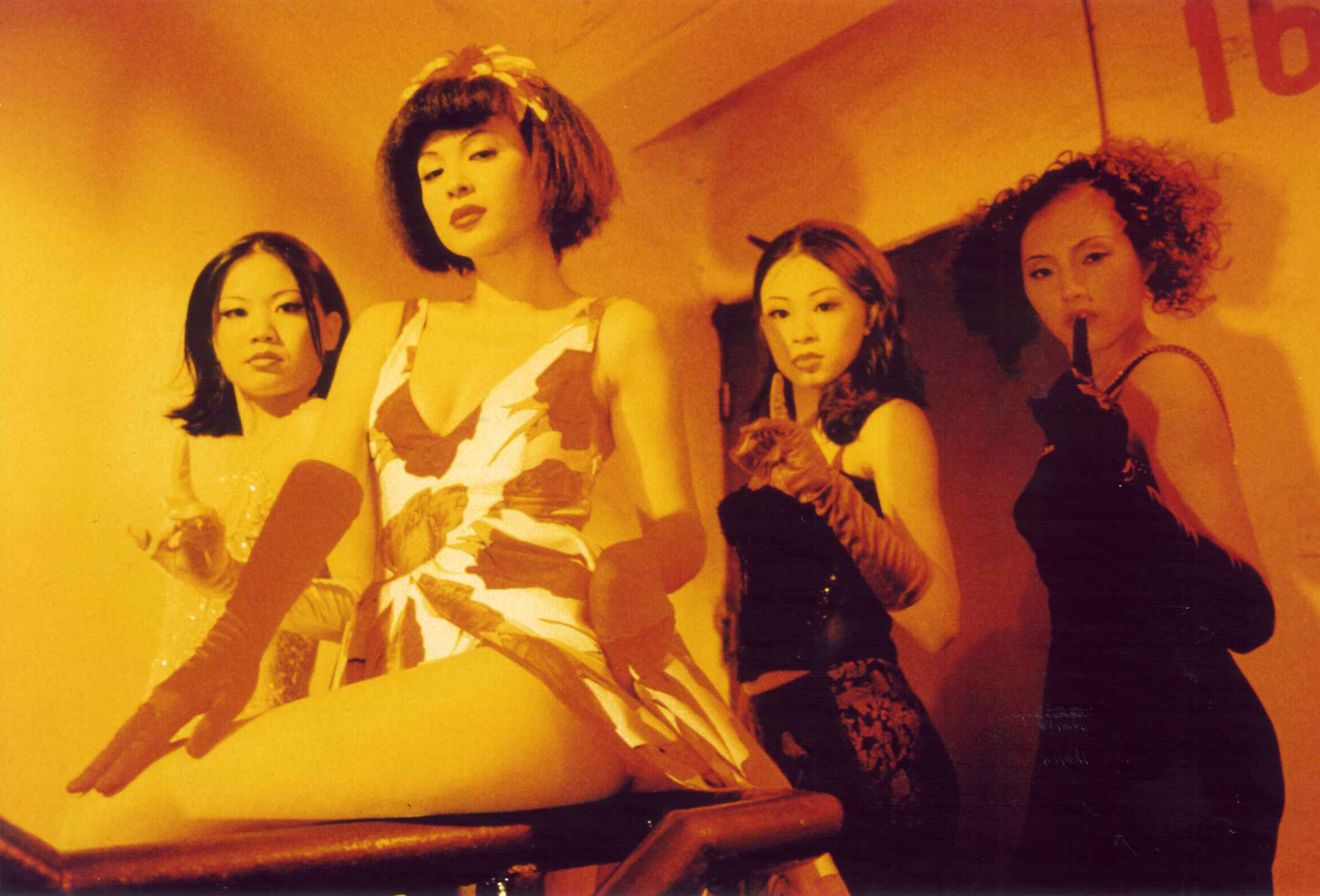

The creepiest part of The Hole, however, is not its obsession with its characters, or the cockroach-spread disease that has wiped out the citizens of Taiwan, but the glamorous musical numbers interspersed with the quiet pain and woe. These scenes, where Kang envisions his downstairs neighbor, played by Yang Kuei-mei, lip-syncing to Grace Chang songs, are particularly striking and really drive home the film’s dark nature with a touch of flair.

Both films are remarkably edited. Editor Wang Chi-yang has an eye for giving good shots the time they need to sink in. Both of these films are extremely slow, and sometimes this makes them admittedly boring, but if viewers can make it past the act two mark they will find themselves rewarded by even more power in the drama than before. Even if the films are sometimes slow, and even if the shots have very little movement, the audience can still be interested the entire time through. The precision and skill of Wang Chi-yang is on point, and he allows the films to find their near-perfect pacing. He maintains just enough intrigue through his careful cuts to keep the audience engaged the entire time.

The sound design is no different. At many points, the ambient street and city sounds lulls the audience, and this is another one of Tsai Ming-liang’s greatest tactics. Through audio design, he forces the viewer to follow and connect with the characters. He further uses this to his advantage in settings like the roller rink or the arcade; with loud, sudden bursts of noise, he pulls the audience back into an active understanding of the film. However, while the sound design for both films is brilliantly and meticulously done, Rebels of the Neon God’s score is severely lacking. The choice to have the film nearly musicless is bold, and this creative distinction is ruined by the bland music added. It is relatively catchy, but in the end, repetitive, uninteresting, and does not fit the tone. This is balanced by the hard-hitting musical numbers in The Hole, which are the opposite, a highlight of the film.

The Hole is a perfect match for Rebels of the Neon God. Not just because their cinematography and composition styles align accordingly, or because they both deal with weird and out-of-the-ordinary topics, but because they follow the same themes: —the aimless, momentumless people and what they do with their lives. Tsai Ming-liang films are all about lives—the day-to-day goings on of his characters, the conditions in which they live, and the things they will do to achieve their goals. This director does not romanticize or dramatize life.

Tsai Ming-liang is one of the greatest directors of the past thirty years, as evidenced by his focus on characters, his creativity and knack for bizarre plot elements, and his astounding cinematography. His films are quiet and considerate, leaving room for audience engagement and interpretation; unlike other slow cinema directors, he keeps the viewer captivated and intrigued without sacrificing any of his vision thanks to the great collaborators he keeps close by. Unconventional horror-romance The Hole and bustling city drama Rebels of the Neon God are two top-notch examples of a master filmmaker at work.

Lead Photo Credit: Still from Tsai Ming-liang's Rebels of the Neon God (1992), courtesy of Big World Pictures.

The TeenTix Newsroom is a group of teen writers led by the Teen Editorial Staff. For each review, Newsroom writers work individually with a teen editor to polish their writing for publication. The Teen Editorial Staff is made up of 5 teens who curate the review portion of the TeenTix blog. More information about the Teen Editorial Staff can be found HERE.

The TeenTix Press Corps promotes critical thinking, communication, and information literacy through criticism and journalism practice for teens. For more information about the Press Corps program see HERE.