Through the Lenses of "American" Art

Review of American Art: The Stories We Carry at Seattle Art Museum

Written by Teen Writer Maitreyi Parakh and edited by Audrey Gray

The same contradictions and cohesion that makes art worth exploring is the same thing that makes it so difficult to define. While the American Art: The Stories We Carry exhibit at the Seattle Art Museum presents it as a question to be answered, it would be more accurate to consider it a framework to view each piece by. Within each piece and within each question, the exhibit presents nuance–what is American art specifically? Who gets to decide? Curated by Inye Wokoma, American Art: The Stories We Carry highlights the uniqueness of different racial identities and backgrounds in America, especially in the Pacific Northwest, and perceptions of them here and beyond. It presents Indigenous and African-American ties to the land, contrasted with the perspectives of the first colonists in the area. The gallery uses this contradiction to display the relationship and responsibility settlers have to Indigenous people in the area and how that compares with the connections they have with the land.

The gallery opens with two landscapes paintings with similar settings: Mount Rainier, Bay of Tacoma – Puget Sound (1875) by Sanford Robinson Gifford and Mitchell's Point Looking Down the Columbia (1887) by Grafton Tyler Brown both portray the terrain of the Pacific Northwest, with majestic mountains towering in the distance and expansive waterways laid out beyond. The scenery juxtaposes with the role of Indigenous people in the paintings—in Wokoma's words, Indigenous people are considered to be "wild and remote," but even more than that, their role in the environment is significantly diminished. In both paintings, Indigenous people are pictured as diminutive and less than, with their faces blurred out and the focus being on the landscape over the people present on it. They're disregarded on their own land, despite Wokoma's note that land serves as both an origin story and a significant cultural element for many Indigenous groups. Clearly, landscapes weren't the paradigm of impartiality they masqueraded as. This dynamic sets the stage for the rest of the exhibit, which reclaims the role of Indigenous people and changes the position from which viewpoints are centered.

A main consideration of which perspectives were presented in the gallery was whether they served to limit or deepen the pieces shown. Two works that demonstrated this clearly were A Trapper (1910) by Newell Convers Wyeth and A Moment of Suspense (1911) by Henry Farny. At first glance, the position and the environment of each subject is strikingly similar. However, after poring over the details, I noticed the differences in the expression and intent of the characters in each piece. Wyeth's trapper is set on a mission, almost tinged with desperation, with the harsh angles of his posture and stance, starkly in contrast with the curious exploration on the Indigenous subject in Farny's work. Wyeth emphasizes the expansion of settlers west, while Farny centers the Indigenous experience on their own land–each painting feels like switching the lens to view the same story through a different set of eyes.

Of course, as Wokoma says, "both [artists] draw from their personal and family histories in their treatment of their subjects." Wyeth's family had ties to several military conflicts over the years, including the French-Indian War. With this historical background, the reason for his subject’s harsh bearing is more discernible, tied to Wyeth's own strained relationship with Indigenous people. In contrast, Farny, who was raised near a Seneca reservation, paints his subject in an empathetic and more understanding light. The exhibit explores this idea; that nothing can be presented in a way that does it justice without the creator having a direct connection and relationship with the subject.

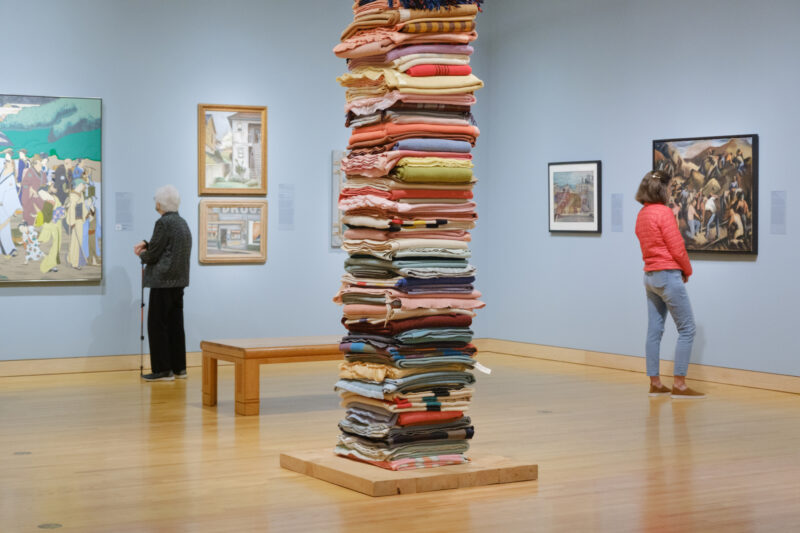

The work that best lends a further perspective to this concept is Blanket Stories: Three Sisters, Four Pelts, Sky Woman, Cousin Rose, and All My Relations (2007) by Marie Watt, located in the center of the exhibit. A stack of blankets towering over each visitor, Blanket Stories stands equidistant from each of the other pieces in the room and demonstrates, according to Wokoma, how "we all share a history and a relationship with Indigenous communities." Blanket Stories is demonstrative of the artist's connection with the subject, especially as blankets hold a heavy meaning in Native communities. Though Wyeth's A Trapper doesn't directly address Indigenous people, the subjects left out convey just as much information as those included. The choice to leave them out of a piece meant to be on their own land, or devaluing their importance, says as much about the role they play in maintaining the connection to the land as it would've if it had been explicitly stated.

Though the content of these pieces demonstrates how bias shapes and informs art, an even more underlying form of prejudice can be found in interactions over the years with artistic mediums. Euro-American paintings and sculptures were placed on pedestals while the artistic merit of Indigenous customary belongings, totem poles, ceremonial weavings, masks, and more were disregarded by colonists, and later, by many of us in the modern day. The dominant perspective history is viewed from continues to influence the art world, with our gaze subconsciously emphasizing the outlooks of the settler-colonists who imposed themselves on Indigenous people, even if we claim to consider each viewpoint equally. The gallery itself compares the works of Bierstadt and Wyeth to the cultural pieces made by Indigenous people, challenging the viewer by asking them to think about their perception of the difference between the two.

Though all of the pieces in The Stories We Carry are considered art, the exhibit posits a timeless question: what is art really? The response to this question is heavily reliant on who is answering. When we look beyond the surface, the underlying question reveals itself—which implicit decisions and assumptions have become a part of who we are and how we’d answer this question? Though there are many ways to attempt to define art, we can never truly discover all of the answers. Art is changing constantly. As we begin to understand more about the stories that define us and allow ourselves to accept multiplicity within who we are, our perception of art expands and evolves. In the end, all we can truly know is this: art is within us, and art is the whole of who we are.

American Art: The Stories We Carry took place at Seattle Art Museum on October 20, 2022 - January 19, 2023. For more information see here.

Lead Photo: Blanket Stories: Three Sisters, Four Pelts, Sky Woman, Cousin Rose, and All My Relations, 2007, Marie Watt.

The TeenTix Newsroom is a group of teen writers led by the Teen Editorial Staff. For each review, Newsroom writers work individually with a teen editor to polish their writing for publication. The Teen Editorial Staff is made up of 6 teens who curate the review portion of the TeenTix blog. More information about the Teen Editorial Staff can be found HERE.

The TeenTix Press Corps promotes critical thinking, communication, and information literacy through criticism and journalism practice for teens. For more information about the Press Corps program see HERE.