Using Film as a Lens for History: Two Views on Fritz Lang’s Metropolis

Review of Metropolis

Written by Teen Writer Yoon Lee and edited by Teen Editor Lily Williamson

The 1927 Fritz Lang film Metropolis is among the most influential films to ever exist, spawning discussion and setting standards that would influence the entire science fiction genre going forward. However, as is the case for any near-century-old film, many aspects are impossible to address without considering the historical context of its creation. As such, interpretations of this film from any time period can be an opportunity to further understand its context, and the viewpoints of those that viewed it in its prime. Among the best ways to pursue this opportunity is to view the reviews and critiques by audiences of the time. Of the multitude of high-profile figures that viewed and spouted their (often disapproving) takes on “Metropolis,” among them prolific science fiction author H. G. Wells, an often overlooked 1929 review is that of Shim Hun. This oversight is both due to the non-Western nature of the review, being written by a Korean, and due to Shim being an author targeted by Imperial Japanese censorship and subjugation.

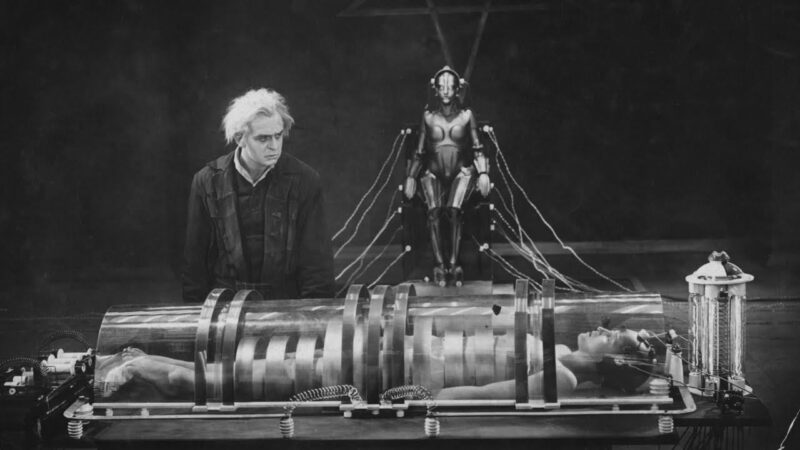

Metropolis is a German science-fiction drama that presents a futuristic utopia existing above a bleak underworld populated by mistreated downtrodden workers. When the privileged Freder discovers the poor, and often fatal, conditions under the city, he becomes intent on helping the workers. He befriends the rebellious teacher Maria, who preaches to the workers of Metropolis, but this puts him at odds with his authoritative father Fredersen, master of Metropolis. Fredersen seeks out the deranged genius Rotwang to impersonate Maria so that the workers can be fooled and controlled.

Some parts of the movie are easily recognizable through modern lenses. The soundtrack is subject to the timelessness of music, and therefore available for analysis today. “Metropolis” composer Gottfried Huppertz’s usage of music follows the silent movie model of orchestral music accompanying on-screen actions but is unique in this movie as the movie was partially structured around the soundtrack--Huppertz often played piano arrangements of his music while Lang directed the actors. Other than the impeccable timing of music to actions shown on screen, and the classical skill of Gottfried’s Wagner- and Strauss-inspired work, there are several musical “cameos” that aid in the movie’s messaging. Stand-outs include a minor-key version of “La Marseillaise” accompanying a French Revolution-esque worker’s uprising, and the medieval Christian chant “Dies Irae” preceding said uprising, Maria’s replacement with a robotic doppelganger, and the appearance of the 7 Deadly Sins. The latter, interestingly, is the most quoted musical leitmotif in history, showing up in places such as Holst’s The Planets, Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, Carlos and Elkind’s score for The Shining, Williams’ score for Star Wars (and Home Alone), and Zimmer’s score for The Lion King.

The architecture, too, is interpretable through modern artistic understandings. The various models and miniatures are easily recognizable as art deco, though different from its contemporaries. Much is more modernistic, rectangular, and blocky, and eerily accurate to modern aestheticism. I, for one, was shocked to see a bedside lamp in the film that I would expect to see in an IKEA.

However, there are several aspects of the film that simply cannot, or should not, be separated from their historical context, which is where Shim’s review takes relevance. When first viewing the movie I was intrigued by the acting, which was more dramatic and theatrical than what I viewed as conventional. The exaggerated motions, facial expressions, and overall pacing of the movie and its acting were far closer to a play or an opera than a motion picture. As such, I could not quite gauge how each actor performed relative to their time, as I could not tell what was overacting, underacting, or simply good acting. Shim provided his view that most of the actors were largely mediocre and seemed overwhelmed by Lang’s staggering setpieces, but “the one who stood out among them was Miss Brigitte Helm.” Shim and I share the sentiment that her performance as Maria is convincing, whether it be in her serenity, sincerity, or panic. Furthermore, her double-role as the Machine Man, Maria’s doppelganger, is sincerely frightening and appropriately disturbing--her arrogant and chaotic cackles while being burned alive, and alien-like movements in the psychedelic dancing scene, are truly impressive.

One important point, however, is the socio-political messages Lang wove into the fabric of the film, particularly the idea of inter-class cooperation and the need for a “mediator” between them. In particular, the idea that the upper class is the “brain” and the working class the “hands”, so that a mediator must be the “heart”. This is a message many see as almost a “cop-out” among the more directly revolutionary, “seize the means of production”-style works of art from that era. Shim picks this thread up, being disappointed to “see the story end with labor-capital cooperation.” He later goes on to say that “Metropolis” is a “strong and powerful expression” that even “radical red Russia” would not be able to express to the same degree. This view on Metropolis’ beliefs betrays Shim’s other, more well-known endeavors: revolutionary writing against the Japanese occupation of the Korean Peninsula.

Shim was a novelist, poet, and playwright, born in 1901 and dying of typhoid fever in 1936. In his short life, he wrote several novels, short stories, plays, and poems. He constantly held a vision for his country’s future freedom, creating the Sangrok movement that encouraged young, educated people to educate and organize the rural populace. These ideas and experiences are reflected in his belief that an oppressive upper class, as shown in “Metropolis” should be overthrown, and was thus disappointingly missing from said movie. Even his short review of a German movie, written two years after it came out, in outdated Korean, and first released nearly a century ago demonstrates his situation and personal opinions.

“Metropolis” continues to stand the test of time, and its ability to offer a window into the world that is nearly a century past is only aided by viewing its contemporaries’ views on it. In that view, Shim’s review of “Metropolis” offers both a further appreciation for the movie, and insight into its context.

Lead photo credit: Alfred Abel and Brigitte Helm in Metropolis, 1927.

The TeenTix Newsroom is a group of teen writers led by the Teen Editorial Staff. For each review, Newsroom writers work individually with a teen editor to polish their writing for publication. The Teen Editorial Staff is made up of 6 teens who curate the review portion of the TeenTix blog. More information about the Teen Editorial Staff can be found HERE.

The TeenTix Press Corps promotes critical thinking, communication, and information literacy through criticism and journalism practice for teens. For more information about the Press Corps program see HERE.